A Leap of Faith

This year Siena Heights celebrates the 40th anni-

versary of offering adult

degree-completion pro-

grams. From its humble beginnings in Southfield at a former elementary school (left), the pro-

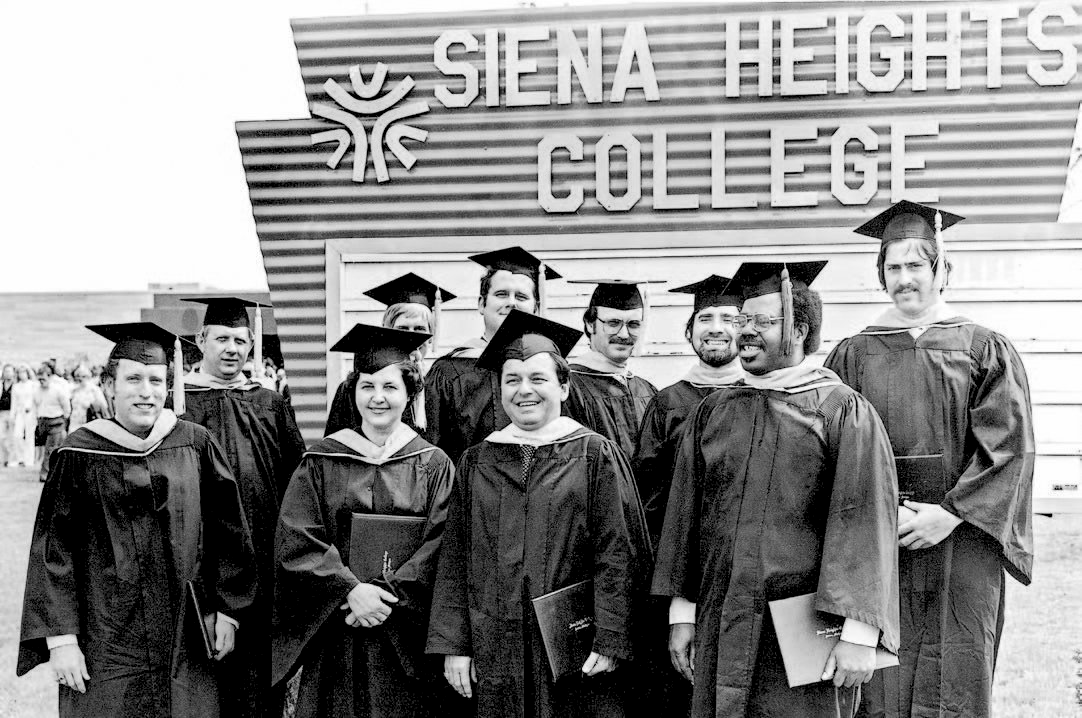

gram now boasts more than 60 percent of all SHU graduates each year. The ultra-successful Bachelor of Applied Science degree graduated its first students (below) in the late 1970s and has made degree-completion a reality for students from all age groups and backgrounds, furthering the Siena Heights Mission in the process.

Concept of Educating Working Adults Turns into the College for Professional Studies

As the 1960s were known as a time for social experimentation in America, the 1970s had Siena Heights experiencing its own period of educational “counterculture.”

In 1970, then Siena Heights College had named its first lay president, Dr. Hugh Thompson, and was transitioning from all-female student body to a coeducational one. If that evolution wasn’t difficult enough, Thompson brought more of a business and career-focused educational approach to campus, ruffling feathers of some liberal arts-focused faculty and staff of the time.

Thompson’s vision included starting

associate’s degree programs that had a fingerprint more like a two-year technical college, not a private, Catholic, four-year institution. Yet some of these

programs not only survived, but grew and evolved. Soon, the unique Bachelor of Applied Science degree was born.

That degree became the “seed” that allowed Siena Heights to plant campuses around Michigan. First, in Southfield, then spreading to places like Benton Harbor, Battle Creek and Monroe.

Even a separate college—the College for Professional Studies—was eventually created to manage the growth of these off-campus programs. Currently, more than 60 percent of SHU’s graduates now come from a site other than the Adrian campus.

Ironically, the program that some people initially wanted to reject has become one of Siena’s distinctive educational cornerstones because of its unique way of bringing the Dominican, liberal

arts tradition to a once-overlooked segment of students.

As SHU adult degree completion celebrates its 40th anniversary of opening its first off-campus site in Southfield, Reflections is taking a look back at how it all got started, and where it is at today.

The Community College of Lenawee County

When Hugh Thompson arrived as president of Siena Heights, he noticed there was not a two-year degree option in the county. He saw that as an opportunity to increase not only the educational programs Siena Heights offered, but to add needed students.

“One of the things that became real clear when I got here, was (Thompson’s) vision of Siena,” said Norm Bukwaz, who arrived on the Adrian campus in 1974 to teach sociology. “There was no community college in Lenawee County, so Siena was still going to be Siena in the way it has always been, but it was also going to be Siena in another way: the community college of Lenawee County.”

New associate degree programs were created in concentrations such as fashion merchandising, hotel and restaurant

management, electronic engineering technology and criminal justice.

“Most liberal arts schools don’t have these associate’s degrees, but Thompson came out of a career (orientation), instead of a more traditional liberal arts orientation,” Bukwaz said. “Business was going to be big.”

The Beginnings of the BAS

With all these students graduating with applied associate’s degrees, there was a growing demand to offer a four year

option. Bukwaz said the educational leaders of the time, led by Director of Community Education Dr. John Miller, developed the Bachelor of Applied Science degree concept.

“They had been thinking about it for a broad range (of programs),” said Bukwaz, who left the sociology classroom after one year and became the co-op coordinator of the new Applied Science Division. “Fundamentally, the argument became, ‘why can’t (the BAS) be a part of the mission of a liberal arts school?’ To take people with technical back-

grounds and make them more humane technicians? Broaden their intellectual horizons. The employers I had made connections with said that what technical people need are communication skills, interpersonal skills, critical thinking, and ethical sensitivities. … It looked like it had potential.”

The Board of Trustees agreed, approving the BAS in May 1975. Soon, electronic engineering technology students from the RETS Electronics School traveled from Detroit to Adrian to complete their degrees.

“RETS was the one that really got (the BAS) going,” Bukwaz said.

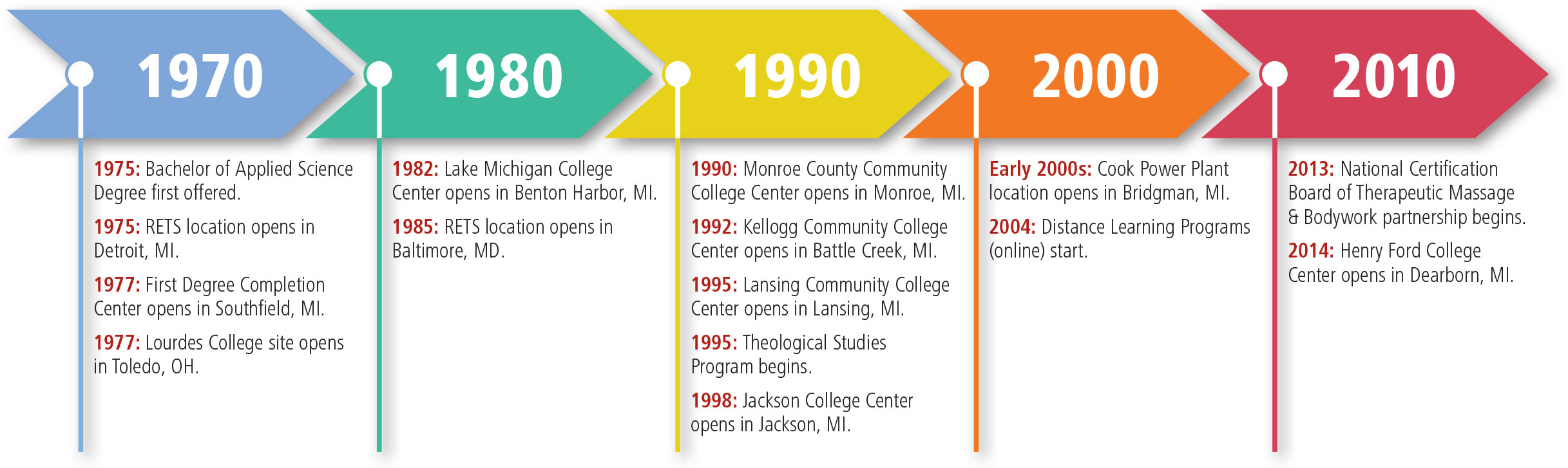

College for Professional Studies Historical Timeline (click to see larger)

Breaking the “European Model”

It didn’t take long for RETS officials and students to begin another conversation with Siena Heights officials about

bringing the adult degree completion programs to them. At the time, the thought of offering classes at locations other than the traditional brick-and-mortar campus was nearly unprecedented.

“Colleges and universities have always been the European model, of here’s this university or college, and everybody who is going to be educated is going to come to us, and it’s going to be take place within these walls,” said Deborah Carter, dean of the College for Professional Studies. “We were the first private college in Michigan to do this, and Siena Heights College said, ‘Yes, we think this is worth pursuing and we are going to go ahead and do this. And we will do it as a mission-centered endeavor.’ In order to open ourselves up to the possibility that it could be done well in a different format took a leap of faith.”

Bukwaz, who was named the first director of the BAS Program—and still has that title today—said the first classes in the Detroit area were offered at RETS, the Westinghouse Corp. and a machine and tool company in 1975.

In 1977, thanks in part to a $1 million or so grant authored by Tom Maher for advanced institutional development, Siena Heights opened its first permanent center in Tower 14 of the Northland Shopping Center in Southfield.

“We were either on the 11th or 12th floors,” Bukwaz said.

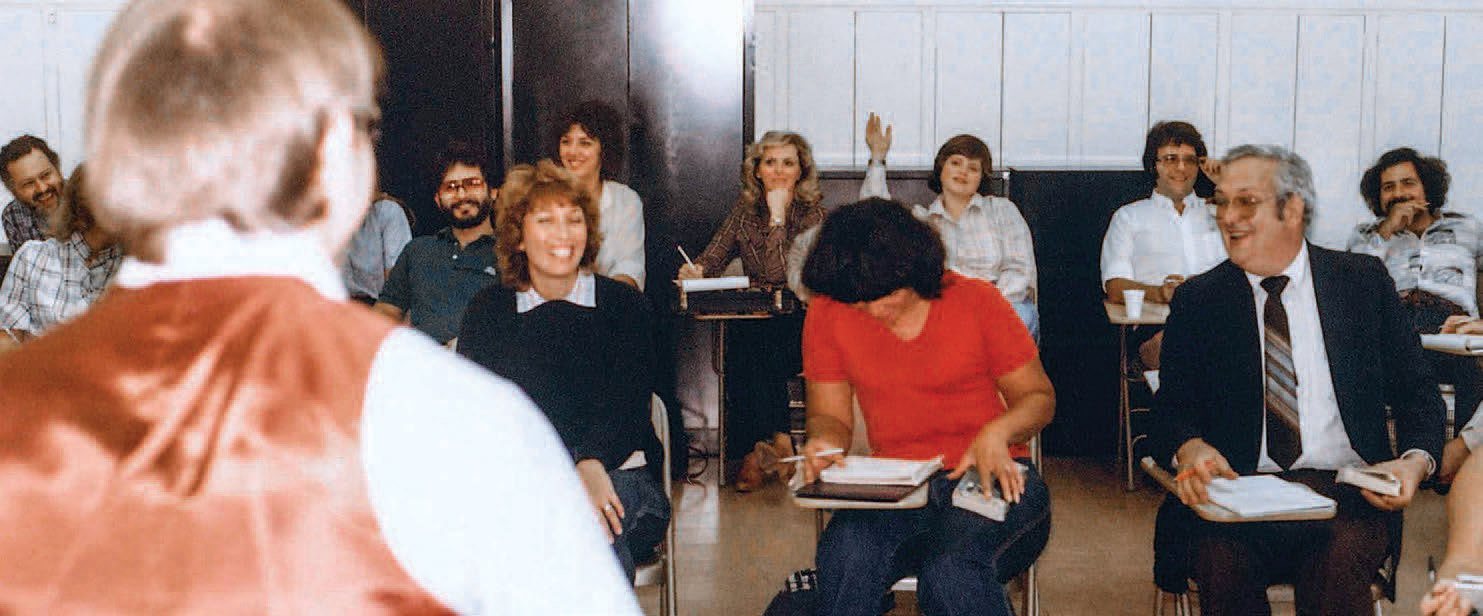

Program delivery was also much different than the traditional, 15-week model of the Adrian campus. Now, classes were offered in eight-week formats, often at night or on weekends to accommodate working adult students.

One of those students, Steven West ’79 (read his full profile here), said the Southfield program was a “good opportunity.”

“I had actually graduated from tech school and wanted to get my college degree,” said West, an EET major at RETS who received one of the first BAS degrees from the Southfield center. “They literally just got (the program) started. … It was a really good experience, and I think we were all kind of learning the process at the time.”

Bukwaz said the Southfield program consisted almost exclusively of EET and nursing professionals (RNs and CRNAs).

He said the BAS model worked well from the start, and filled a need very few other institutions could provide.

“That’s the problem four-year schools have always had in designing four-year programs,” he said. “(The BAS) is a program for practicing professionals with Associate of Applied Science degree backgrounds. … (AAS students) live in a credentialistic world. They represent the ‘other’ transfer student. The idea is that a whole category of AAS grads out there needed a program so they could build a baccalaureate degree.”

The Community College Partner Model

Bukwaz was the dean of Admissions and Off-Campus Pro-

grams when he received a letter from the president of Lake Michigan College in 1982. LMC was looking for a new partner to provide bachelor’s degrees in business on its Benton Harbor campus. The program also needed to be very transfer-friendly. After some conversations, Siena accepted the offer to partner with LMC. More than 33 years later, Bukwaz said it has become the “model” for the CPS/community college partnerships.

Carter, whom Bukwaz hired to staff the LMC location—and eventually replaced Bukwaz as dean of CPS in 2000—agreed. She said there were some built-in advantages of being onsite at another institution.

“Being on a community college campus, we have been able to hire the cream of the crop faculty who are full-time, many who are PhD held in those various locations,” Carter said. “It’s the ideal setting for faculty recruitment in the setting of the community college. They have a real understanding of the student from the community college.”

Siena Heights expanded this model to several other community college locations in the state. Currently, SHU also has centers in Battle Creek, Dearborn, Jackson, Lansing, Monroe as well as an award-winning online program.

Back to the BAS

Although CPS offers a number of degree programs such as business, accounting, professional communication and multidisciplinary studies, the BAS is still the most prevalent.

“I think that the Bachelor of Applied Science degree is successful at Siena Heights because of some basic institutional assumptions,” Carter said. “It’s so successful because we have been able to, with Norm’s enormous help, examine all of the current health, trade and occupational associate degree programs that have fit into the model of an inverted major. An inverted major means that the major coursework has already been accomplished before coming to us.”

“If you think about it, if we didn’t have the BAS, we probably wouldn’t have the off-campus programs,” Bukwaz said. “That’s been the opportunity. If there is one program that has been distinctive about Siena Heights (it’s the BAS).”

Pat McDonald during the celebration of Siena Heights becoming a university in 1998.

The map they are holding shows SHU’s locations in Michigan at the time.

And West agrees that bringing a liberal arts education to a non-traditional student population is a good thing.

“One of the classes I took (at SHU) was the philosophy of art,” said

West, who has spent more than 30 years as an executive in the tele-

communications industry. “It really got me interested in impressionist art. I did my paper on impression-

ism, and since then I’ve really been a big fan of (impressionist art.) That was something I specifically took out of that.”

Carter said the flexibility of the BAS is also one of its strongest features.

“What has constantly been the advantage of the Bachelor of Applied Science degree, is it has never been tied absolutely to one program,” Carter said. “We have been able to meet people where they are and what they’ve done before. That’s huge.”

Providing credit for past work experience was another important facet of the adult degree completion program. Bukwaz credits an unlikely source—the late teacher education faculty member Sister Eileen Rice, OP—for the development of that concept.

“One of her special areas … was in vocational education for state certification for vocational teachers,” he said. “She was a leader in the state (to award credit for work experience).”

6,300 and Counting

Since the BAS started, Siena Heights has graduated approximately 6,300 students from the program. That’s roughly 27 percent of all of SHU’s baccalaureate degrees since opening its doors in 1919.

Currently, BAS graduates comprise about 60 percent of all CPS graduates. And those numbers are expected to rise.

Carter credits the overall achievements of CPS to her faculty and staff, especially the academic advisors who serve the needs of the adult degree completion student on a daily basis.

“The absolute key to the success of CPS is our professional advising staff,” she said. “To have an army of people who are really shepherding students, that’s big. That resonates with people. That whole customer service model is very Dominican.”

“I think it’s worked out pretty good,” Bukwaz said of the CPS model. “And we have some tremendous stories now. … (Adult) students need to be educated. We’ve made some differences.”